Alexandra Gruca-Macaulay

Why the sudden rush? That question is on the minds of many in response to the Lansdowne Partnership Sustainability Plan and Implementation Report that sought approval from City Council on June 8th as The Mainstreeter was going to press. The controversial plan (known as “Lansdowne 2.0”) would see the City embarking on a $332.6 million reconstruction project at Lansdowne Park, involving the redevelopment of the north side stadium stands, the construction of a new underground event centre, as well as a retail podium. To help fund the project, the development would add 59,000 square feet of retail space, and 1200 residential units situated within three residential towers ranging between 30 and 46 storeys.

The City’s financial strategy includes a scheme to channel property taxes from the new retail and residential development towards construction debt pay-down. Given the complexity of the financial arrangements, the number of immediate concerns that Lansdowne 2.0 has already raised, the absence of prior consultation, and the fact that this Council is in its “final days” in office, Councillor Shawn Menard – the ward councillor for Lansdowne – has asked that Council defer decision-making on Lansdowne 2.0 until a robust public consultation on the proposal has been allowed to take place.

The Lansdowne problem of financial viability – the City has received $0.0 return on investment to date

In 2012, a plan to revitalize Lansdowne was approved by Council. The Lansdowne project was anticipated to become a showpiece for public/private development partnerships where a group of private developers – under the umbrella of the Ottawa Sports and Entertainment Group (OSEG) – would partner with the City to bring financial health and community vibrancy to Lansdowne. The City, at a cost of $166.0 million, redeveloped the football stadium, especially the south-side stands, and made a number of improvements to the Civic Centre. OSEG committed to its ownership of the Ottawa Redblacks CFL team, to the maintenance of the stadium and the Civic Centre and to managing the construction and operations of new retail space as well as two new residential condominium towers.

Viewed from across the Rideau Canal, Lansdowne’s showpiece, the storied Aberdeen Pavillion, would be engulfed by three surrounding massive residential towers if Lansdowne 2.0 is approved by City Council. Photo by John Dance

The City still owns the entire 40-acre Lansdowne site, but, under the partnership agreement, leases portions of it to OSEG. Within this leasing arrangement, OSEG has responsibility for the cost of maintenance of the leased facilities, and each of the City and OSEG were to share in the revenues that were expected to be generated by the operations of the facilities within the partnership. These revenues, under what is called the “waterfall agreement,” were to be divided between the partners after meeting a series of financial tests. From the start, the financial arrangement fell short of expectations – to date, the City has received $0.0 return on its investment under the waterfall, and OSEG has claimed that it has needed to invest more than it anticipated under its obligation to maintain the facilities. The pandemic amplified the financial strain on the partnership, and, in July 2021, Council directed City staff to work with OSEG and with community stakeholders to develop a plan to bring the City/OSEG partnership into financial viability.

Sounding board – no consultation before release of plan

On December 9, 2020, Council directed City staff to create a group of stakeholders – the Sounding Board – that would include representatives from neighbouring community associations, including Old Ottawa East’s, and to consult and engage with the group as plans for Lansdowne were developed. Although the Sounding Board was formed, City staff and OSEG moved planning behind closed doors, and despite regular requests for meetings and updates from Sounding Board representatives, City staff did not consult during the course of drawing up plans for Lansdowne 2.0. Instead, after almost a year of silence, the City released its 102-page report one week before tabling it with the City’s Financial and Economic Development Committee (FEDCO) for approval. When questioned why the Lansdowne 2.0 report was tabled prior to any consultation with Sounding Board community representatives, Stephen Willis, the city’s General Manager, Planning, Real Estate and Economic Development, cited protracted confidential negotiations with OSEG and said that the City had “run out of time.”

In response to the exceptionally short time frame to digest the implications for what would be the City’s third largest debt undertaking after phases 1 and 2 of the LRT, Councillor Menard asked at the May 6th meeting of FEDCO whether one of the committee members would read in a motion that essentially would have seen the report’s recommendations “received” rather than “approved” and would have mandated the City to begin robust public consultation prior to making any decisions. No member of FEDCO was willing to read the motion in, and the chair, Mayor Watson, refused to allow Councillor Menard to read out the contents of the motion. FEDCO approved the report, and it is now tabled for City Council’s June 8th meeting.

If approved, the Lansdowne 2.0 plan would be built in stages; the 5,500 seat Event Centre would be constructed first with completion in October 2024, followed by the new north side stands finished in 2027, and the residential towers, which would begin housing residents in 2027 and be fully built by 2029. Image Supplied

The Lansdowne 2.0 Event Centre and Stadium—projected losses

The Lansdowne 2.0 report, while observing that the north stands and Civic Centre are structurally sound, claims at page 79 that without a redeveloped stadium and a new events centre, “it will be extremely difficult for the partnership to meet its…financial sustainability requirements.” This claim seems to rest on the view that although functional, the stadium and event centre are not sufficiently up to date “to impart an exciting user experience and to attract new visitors to the site.” As a result, the report has asked Council: to approve

the recommended business model andfinancial funding strategy that would see the construction of the new event centre and redevelopment of the north side stands; and to establish budget authority for the cost of construction and preliminary works in an amount of $332.6 million.

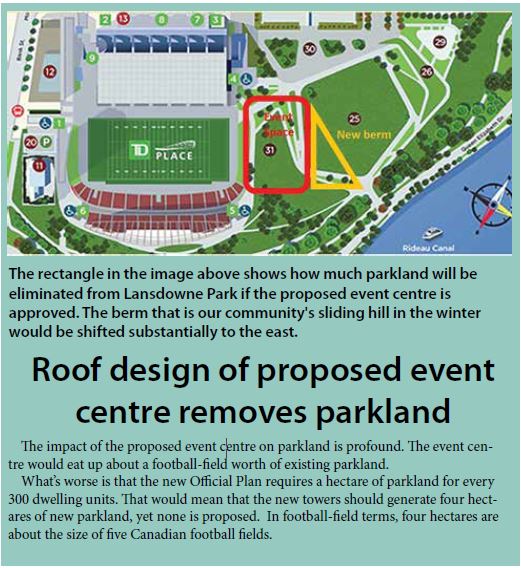

While the existing Civic Centre seats 9,862, the new event centre would have a reduced seating capacity of 5,500, and questions have been raised as to whether a smaller event centre is what Ottawa’s growing population needs. This new event centre would be relocated under the west end of the stadium’s field, beneath the grassy berm where today people enjoy sitting in the summer and sledding in the winter. The sunken roof of the event centre would be “grassy” but would not be able to support the weight of people on it, resulting in the removal of 58,000 square feet of useable park greenspace from Lansdowne.

The Lansdowne 2.0 business and financial plan is dense, but at its heart is the claim that a new event centre and north stands are necessary for a viable partnership. Although touted as critical to financial sustainability, the stadium and new event centre – somewhat alarmingly – are projected to lose $84.0 million over the life of the partnership. When questioned about this expected loss ($124.0 million when 67’s hockey is included) during the May 6th FEDCO meeting, the City’s Deputy Treasurer, Isabelle Jasmin, replied that while these components will “not be as profitable” as some of the others, the proposal must be understood as a complete package where the anticipated profitability of the Redblacks, and especially of the new retail operations would offset the event centre/stadium operating losses.

Lansdowne 2.0: Lansdowne 1.0 on a larger scale

As the City would be responsible for the entire cost of construction of the event centre and north stands, OSEG presented a business case for offsetting the City’s costs of construction and debt servicing. To this end, the report proposes that a new 100,000 square foot retail podium be constructed above the north side stands to replace the existing retail space located there. At a cost of $40.0 million, the retail podium would increase the retail space by 59,000 square feet. The City would fund 25% of the cost of the construction of the retail podium directly and would guarantee OSEG’s loan for the remaining 75%. The City therefore would take on 100% of the risk of the construction debt for the retail podium, and some have raised the question of whether the City’s guarantee of OSEG’s loan might be deemed a form of subsidy to a private developer.

OSEG’S business plan has reasoned that a considerable increase in retail needs a commensurate infusion of shoppers, which would be provided through the construction of 1200 residential units above the retail podium – confirmed by City staff to involve 3 varying height residential towers that would range between 30 and 46 storeys. Although the plan claims that 10% of the new residential units will be “affordable,” Mr. Willis confirmed that the term “affordable” should be understood as something like “moderately affordable,” more akin to what might be affordable to someone who is “on a nurse’s salary.” As the City would continue to own the land below the podium and towers, it plans to sell “air rights” for the private residential development. In addition, under what the City has termed “property tax uplift,” the City would divert 90% of the property taxes from the new retail and residential development towards the repayment of its anticipated $239.0 million 40-year term project debt.

The public realm: “wish list” but no funding

The spaces at Lansdowne that are not subject to the City/OSEG leasing arrangements, such as the Aberdeen Pavilion and Square, the Horticulture Building, and the Great Lawn, are discussed in the report, but seem not to play an actual role in the Lansdowne 2.0 proposal. The report revisits a number of previously suggested improvements that have accumulated over the years but makes no commitment towards the commencement of their implementation. The report relegates the funding of needed public realm improvements to a future hope of budgetary capital allocations. Indeed, the report seems unaware of the irony that one of the effects of its proposed “property tax uplift” financing scheme would be to divert municipal revenues away from Ottawa city park projects, including Lansdowne’s public spaces.

Implications for Ottawa residents: what are the risks?

The Lansdowne 2.0 proposal espouses a view that a successful future would require “more of the same” but, to be financially sustainable this “more” needs to be a “lot more” – more retail space and especially more people. The City staff report asks that Council approve the financial and business plan, and delegate authority to the City Manager to renegotiate the partnership with OSEG on the basis of the plan’s financial strategy. The main components would then be locked in without the benefit of public consultation, or even sufficient time to allow most citizens the opportunity to begin to understand the ramifications of the proposal.

A good number of issues have been raised since the plan’s release, including financial concerns over the viability of the Redblacks for the full 40-year life of the debt repayment, and particularly, since so much of the financial success of the plan depends upon the retail operations, the risk level that underlies any assumptions around retail operations at a time when the retail sector is moving through a significant post-pandemic transformation.

On a human, quality-of-life scale, serious concerns are being raised about the lack of solutions to what most certainly will be an acute escalation of stress on traffic congestion, the significant reduction of public park space by the event centre’s design at a time when approximately 2,400 new residents would be introduced to the area, and the crowding out of the Aberdeen Pavillion – considered by many to be the historic jewel of Lansdowne – by three visually overpowering towers.

On the heels of the City’s newly minted Official Plan, the Lansdowne 2.0 proposal would require an amendment to the Zoning By-Law, and also legal amendments to the 2011 Ontario Municipal Board Settlement that had set development parameters for the site. The proposal raises critical questions around the issue of whether Lansdowne 2.0 would provide sufficient value to the residents of Ottawa to justify the significant financial and quality-of-life risks that the effects of the proposal would impose.

Most importantly, absent public consultation, there has been no opportunity for the people of Ottawa to consider viable alternatives for comparison and consideration. Without public consultation, and without adequate time to develop a clear understanding of the proposal, it is difficult to understand how this Council, just three months before it enters a period of legislated pre-election restriction on its authority to enter into binding financial decisions, is equipped to answer the question: Is this the best plan for Lansdowne?