Tanis Browning-Shelp

Eight years ago, a group of high-school breakdancers helped Luke Goldsmith shift from feeling lost to feeling fired up about art. He found the students breakdancing in an out-of-the-way corridor of Canterbury High School, where he was enrolled in the vocal program and wondering who he was and where he belonged. “Every teen searches for a purpose and a place to belong,” he says. He approached the dancers apprehensively. But they let him in, and even taught him a few things. One of the dancers, Nicc, also did street art. “He painted funky cubist faces and I was super taken by that,” Goldsmith recalls. “I asked a lot of questions and was pretty camera-happy at the time. Nicc was reluctant to share too much because he was active as an illegal artist. But he eventually invited me to go out painting with him.”

Old Ottawa East artist Luke Goldsmith is finding innovative ways to bridge his graffiti roots with calligraphy and typography. Photo by John Goldsmith

One aspect of graffiti involves putting your name on things that do not belong to you. There are rules, though, even amongst illegal artists—no graffiti on churches, mosques, or houses, for example. But Goldsmith still considers this the “selfish” part of the art form. “It’s about seeing your name plastered all over the place,” he says. “I initially got a rush from painting illegally, but, eventually, I figured out that I could put a thousand percent more time and effort into my art and do it legally.” Ottawa-Gatineau has three legal graffiti walls: House of Paint (HOP) under the Dunbar Bridge, the Tech Wall on Slater Street, and The Worm, a 200-metre tunnel in Quebec. “Tech Wall is for artists of a higher calibre, while The Worm is the most relaxed location, with certain sections designated for the better artists,” Goldsmith explains. “Graffiti artists know to paint accordingly.” According to Goldsmith, most passers-by think the work they do is “cool,” but, occasionally, people threaten to call the police.

In the beginning, Goldsmith copied Nicc’s artistic style. But his mentor eventually encouraged him to develop one of his own. “Nicc gave me two books, Graffiti World and Graffiti Women, both by Nicholas Ganz. “These books introduced me to hundreds of different styles from all across the globe. I found it thrilling to learn about the history of the art form.”

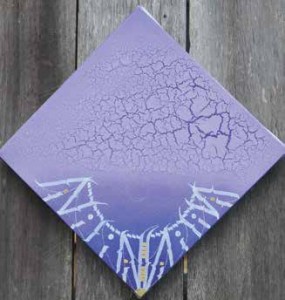

Goldsmith was particularly drawn to the West Coast graffiti style which he describes as “bio organic” or “melty.”

M

According to Goldsmith, it is like machines meeting flesh. “In the beginning, I used this style with its razor-sharp edges and ‘gooey parts’ to get my self-doubt and anxiety out into the world. It was a visual representation of my internal pain.”

He also kept his work open to interpretation. “I like to provoke people into thought.”

After pursuing graffiti art for several years, Goldsmith recently found himself drawn to the refined look of calligraphy. He had a natural love of letters but, at first, he was intimidated by the “fancy pens and nibs.” He particularly liked the ornamentation or flourishes of George Bickham, whose book The Universal Penman is one of the most important works ever compiled on calligraphy.

When Goldsmith was laid off from his job during the pandemic, he decided to explore his new interest further. He studied the World Encyclopedia of Calligraphy and began dedicating himself to the mastery of lettering. He also studied the work of Pakras Lampas, a Russian painter and calligrapher who created the art form of calligraffiti, which combines calligraphy, typography, and graffiti. Goldsmith loved the idea of keeping a sense of graffiti in his calligraphy by making the lettering almost unreadable. “I find the calligraphy attractive, elegant, and eye-catching and I love the idea that lettering and language stem from the core value of humanity communicating.”

ABOVE LEFT AND RIGHT: Several new artworks from Luke Goldsmith include selections from his Sacred Sun series which features spherical shapes and gold leaf lettering painted on wooden paneling. Photos by John Goldsmith

Goldsmith is currently working on two series of

calligraffiti. One series, entitled Seven Deadly Sins, uses a snake-like script on six by twenty-six inch canvasses—long canvasses playing with the shape of snakes. His series Sacred Suns uses gold leaf lettering with spherical shapes in the centres, painted on wood paneling.

Goldsmith’s own style of lettering, as seen in his gold leaf painting of The Mainstreeter newspaper box on Lees Avenue, is inspired by middle eastern and Buddhist lettering. “There is a uniform look to my letters, but each one is unique. Like with the newspaper box, where his lettering spells out the names of 52 Old Ottawa East streets, a person who knows what the lettering represents might be able to figure out his altered lettering like they would when solving a newspaper puzzle. But it wouldn’t be easy. “I like the mysterious quality of calligraffiti,” he says.

![]() To see more of Luke Goldsmith’s art,his Instagram coordinates are @fill.graves.

To see more of Luke Goldsmith’s art,his Instagram coordinates are @fill.graves.